06 Jul Not One but Many: John Muir in Tahoe

The Sierra Nevada mountain range belongs to John Muir, but Lake Tahoe is considered the literary property of Mark Twain, who wrote exuberantly about its crystalline waters edged by serrated mountain tops.

While Muir did not write about Lake Tahoe in any of his formal writings, which would seem to disqualify him from any authorial stake in the Basin territory, his description in an 1873 letter perhaps better encapsulates the wonder and beauty of The Lake better than any writer before or since.

In Muir’s seminal writings, My First Summer in the Sierra (1911) and The Mountains of California (1894), copious ink is spilled over the High Sierra to the south of the Lake Tahoe Basin, but precious little is written about Tahoe itself.

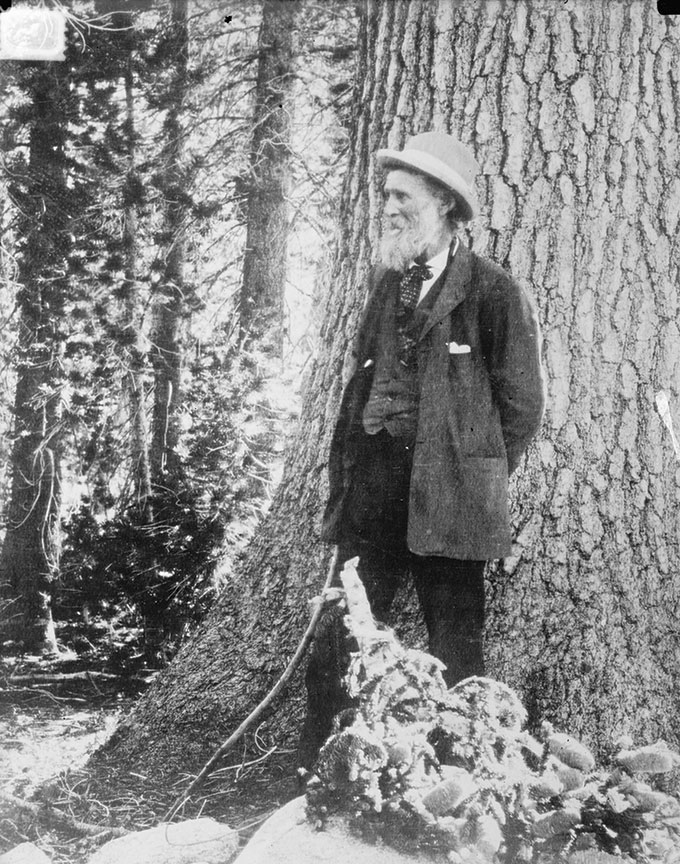

John Muir, photo courtesy Library of Congress,

Prints & Photographs Division

The Jewel of the Sierra is not mentioned once in the former book and only twice in the latter, the first time merely as a landmark to recognize the several mountain passes used by pioneers in their overland treks from the east to California.

The second mention runs as follows: “Lake Tahoe, 22 miles long by about 10 wide, and from 500 to over 1600 feet in depth, is the largest of the Sierra lakes. It lies just beyond the northern limit of the higher portion of the range between the main axis and a spur that puts out on the east side from near the head of the Carson River. Its forested shores go curving in and out around many an emerald bay and pine-crowned promontory, and its waters are everywhere as keenly pure as any to be found among the highest mountains.”

An able description indeed, but it lacks the effusive exuberance with which Muir infused in his prose when cataloguing other aspects of the Sierra, particularly Yosemite, the place to which his heart is most firmly tethered.

Nevertheless, in a letter to a lifelong friend, Muir’s powerful description of the Lake of the Sky testifies to his ardent appreciation of its inimitable beauty.

Muir was born in Scotland, in a quaint coastal town called Dunbar. His family moved to Wisconsin to escape religious persecution and Muir spent a hardscrabble youth, helping his family eke out a living on a farm, while perched on the verge of poverty.

Muir matriculated from high school to the University of Wisconsin, where he studied botany and geology for a couple years before dropping out and heading north to the Canadian wilderness. Much like Twain, Muir fled his home and family to escape the American Civil War. Like Twain he would eventually head west, although their paths were different. After exploring the flora along Lake Ontario, Muir caught a ship down to Cuba, studying plant life and seashells on its idyllic coast before he booked passage to San Francisco, where he landed in 1868.

Unlike Twain, who arrived in Carson City after a prolonged stagecoach trip he recounted colorfully in Roughing It, Muir came by sea. But, like Twain, even though it was not Muir’s final destination, he would come to wonder at Lake Tahoe.

It wasn’t long after landing before Muir was ensconced in the Sierra, but he wasn’t a professional naturalist. Instead, to earn his bread, he spent time working in a sawmill or helping shepherds guide flocks from the foothills to Tuolumne Meadows. During his intermittent bouts with remedial labor, Muir still found time to publish articles about Sierra botany and his conjectures regarding how glaciers were instrumental in forming some of the astounding landscapes unique to the Sierra.

Muir’s published writings captured notice and his fame increased in certain circles, so much so that he decided in 1872 to become a professional writer.

After four years in the Sierra, most of which was spent in Yosemite and the rest of the high country to the south, Muir headed to Lake Tahoe. It is unclear when Muir first saw The Lake, but his earliest mention of Tahoe is in an 1873 letter to Jeanne Carr.

Carr was his lifelong friend and correspondent, a woman he called his “spiritual mother.” He met her initially while at the University of Wisconsin, where her husband was a professor.

Carr and Muir corresponded throughout his travels, and it was through these letters Muir developed his voice as a writer.

From Independence, California, on October 17, 1873, Muir posted a letter to Carr reading: “I have just come down from Mt. Whitney and the newly discovered mountain five miles northwest of Whitney, and now our journey is a simple saunter along the base of the range to Tahoe, where we will arrive about the end of the month or a few days earlier.”

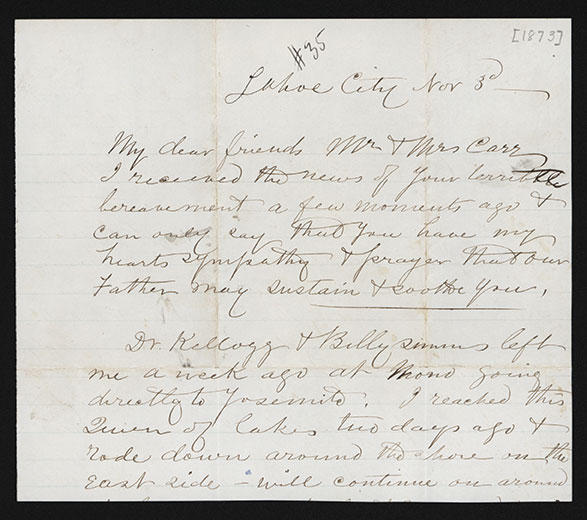

An 1873 letter from John Muir to Jeanne Carr regarding his time at Lake Tahoe

From there, Muir dispatches several letters describing the Sierra’s stunningly precipitous eastern escarpment, the Owens Valley, and various peaks and valleys of the range’s eastern flank.

Then, on November 3, Muir sends Carr a letter from the Tahoe City post office.

It reads: “Dr. Kellogg and Billy Simms left me a week ago at Mono, going directly to Yosemite. I reached this queen of lakes two days ago and rode down around the shore on the east side.”

And then, instead of the sober description of altitude, breadth and depth present in Muir’s formal works, his prose turns lyrical.

“Somehow I had no hopes of meeting you here,” he writes. “I could not hear you or see you, yet you shared all of my highest pleasures, as I sauntered through the piney woods, pausing countless times to absorb the blue glimpses of the lake, all so heavenly clean, so terrestrial yet so openly spiritual.”

This is more akin to the rapture Muir evokes in his writing and the reason he earned his spot in the pantheon of great American naturalist writers along with Thoreau, Whitman, Leopold and Emerson.

“I wish, my dear, dear friends, that you could share this divine day with me here,” he continues. “The soul of Indian summer is brooding this blue water, and it enters one’s being as nothing else does.”

He finishes with a flourish.

“Tahoe is surely not one but many. As I curve around its heads and bays and look far out on its level sky fairly tinted and fading in pensive air, I am reminded of all the mountain lakes I ever knew, as if this were a kind of water heaven to which they all had come.”

This passage is far less popular, far less cited than Mark Twain’s account, which anyone familiar with Tahoe has likely heard.

“As it lay there with the shadows of the mountains brilliantly photographed upon its still surface I thought it must surely be the fairest picture the whole earth affords,” Twain wrote in Roughing It, a quote that has been reproduced in countless political speeches and articles such as this.

Twain’s preceding sentence contains a reductive description of The Lake as a vast oval, whereas Muir’s poetic concession that describing the shape is not only difficult, but futile, is a more nuanced approach.

“Tahoe is surely not one but many.”

Anyone who has spent time in the Basin can relate to this shifting picture of The Lake, the way it reveals aspects of its personality depending on the viewer’s vantage point. Despite being written 140-some years ago, Muir’s words regarding “the queen of lakes” rings very true today.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

1 Comment