17 Dec A Fortune in Tahoe Water

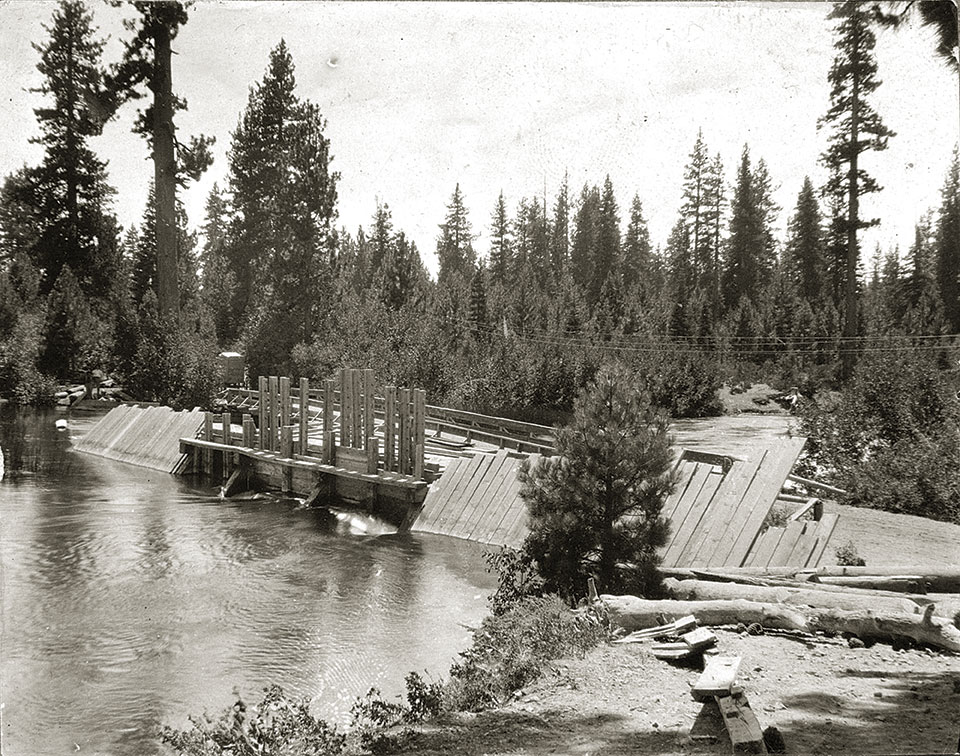

A little-known fact about Lake Tahoe is that it is actually a reservoir. Well, at least it functions as a reservoir. Clearly, Tahoe is a natural lake and its current state is much the same as it was when John C. Fremont and his cartographer first viewed it from a peak in the Sierra Nevada. However, in 1903, when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation began its Newlands Project, which feeds irrigated water to the Lahontan Valley in Nevada, the agency built a dam at the headwaters of the Truckee River. Lake Tahoe Dam, a 17-foot-high structure that is 109 feet long and made of concrete slabs and buttresses, has 17 vertical gates that control the top six feet of Lake Tahoe. This makes nearly 730,000 acre feet of water available for irrigation purposes in Nevada.

California is in its third consecutive year of an intensifying drought, prompting a question about whether the Golden State’s geography is equipped to furnish enough water to sustain a large (and growing) population. Lawmakers locally and nationally continue to grapple with water rights issues and the distribution of an exceedingly scarce resource, often in politically-heated settings, as purveyors, agriculture and environmentalists butt heads over the best ways to use it.

The battle is not new. Contention over water rights in Northern California is as old as the state itself.

Lake Tahoe, which today is viewed as a pristine testament to the peerless beauty of the Sierra Nevada—and not to be trifled with for the purposes of industry—once played a central role in the water wars between California and Nevada.

Von Schmidt’s Repeated Attempts

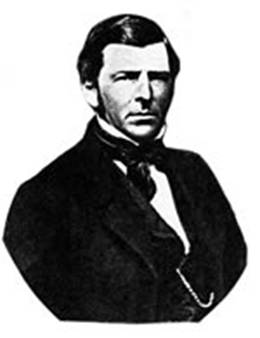

Alexis Waldemar Von Schmidt

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Jewel of the Sierra was viewed as a virtually ceaseless abode of resources—including water—for California and Northern Nevada’s burgeoning habitations.

Certain entrepreneurs also saw Lake Tahoe as a source of personal enrichment that only needed the engineering know-how and the political will to turn one of the world’s largest alpine lakes into some financial account.

One such man was Prussian-born Alexis Waldemar Von Schmidt, a sort of civil engineer cum celebrity, whose problem-solving prowess, self-assuredness and knack for showmanship garnered him the attention and adulation of many of the residents and officials of the nascent California cities that needed his abilities to solve pressing infrastructure problems.

Von Schmidt built San Francisco’s first water supply system in the 1850s when he was part of the Bensley Water Company. When the outfit refused to pay him for a water meter of his own invention, he created a rival company that eventually bought out his former employer.

Having made a fortune in San Francisco and knowing full well following water uphill in California was essentially following the money, he turned his enterprises to the Sierra Nevada and Lake Tahoe, specifically, purchasing a parcel of land adjacent to Lake Tahoe’s sole outlet into the Truckee River and accompanying rights to 500 cubic feet per second of the precious water.

The engineer attempted to convince officials in Virginia City, Nevada, who were presiding over the nation’s biggest silver boom, to finance plans to construct a pipe and pump system capable of conveying water over Spooner Summit, down through Carson City and the Washoe Basin and then up to a reservoir on Mt. Davidson above the Comstock mines.

Officials demurred at the outsize cost of the proposed project.

Not one to quit, Von Schmidt concentrated his enterprising ideas on his old haunt of San Francisco, scrounging five investors to form the Lake Tahoe and San Francisco Water Works Company with the aim of moving the water in Lake Tahoe 163 miles down to the city by the bay via a network of canals, flumes and tunnels. (For an account of his plan to drill through the Sierra to deliver Tahoe water to San Francisco, see Tahoe Quarterly’s 2013 Best of Tahoe edition.)

Von Schmidt promised city officials he could deliver 20 million gallons of water per day from Lake Tahoe if the San Francisco Board of Supervisors could furnish $10 million.

The San Francisco public waxed exuberant with the San Francisco Daily Morning Call stating in an editorial that the project “was decidedly the most stupendous waterworks project ever undertaken on the American continent.”

Conversely, officials from Nevada, cognizant of how wholly the farmers of the Reno and Sparks area were dependent on the Truckee River, were not as impressed. Nevada Attorney General George A. Nourse challenged Von Schmidt’s legal entitlement to the water and many newspapers in Reno and Truckee began to intimate that Von Schmidt might be well-advised to hire armed men to protect his project.

Hints at violence appeared more frequently in the editorial pages as Von Schmidt forged ahead undaunted with site preparation work and the construction of a modest dam at the site of the currently operating Lake Tahoe Dam in Tahoe City.

When the engineer floated his designs to lawmakers in Sacramento and Washington, D.C., he met with a campaign of firm political opposition. However, Von Schmidt was nothing if not persistent and he rejuvenated efforts to garner capital for his ambitious undertakings.

In 1887, as San Francisco was in danger of literally running out of fresh water, city officials once more became enamored of the project, but again the momentum ultimately fell short. The problems that repeatedly arose, according to historians, is that Von Schmidt’s plans consistently appealed more to the imagination than the pocketbook and he could never secure the adequate financing to put a shovel in the ground.

Furthermore, Nevada officials were bent on protecting their interest as the Truckee River supplied irrigated water to a large swath of farmland in Northern Nevada and was the lifeblood of the community’s livelihood. When Luther Waggoner, chief of the San Francisco Department of Public Utilities, visited Von Schmidt’s property in 1900, Nevadans and those living in Truckee and along the North Shore of Lake Tahoe once again began agitating against the city’s attempts to appropriate what they viewed as their water.

“Grandest Aqueduct” Plans Sink

After Von Schmidt’s death in 1906, a prominent San Francisco attorney, Robert Waymire, furthered the engineer’s plans, proposing to install four power plants along the 163-mile channel as it descended the western slope.

When Waymire died in 1910 on a road trip east, where he was set to convince investors to come up with the nearly $45 million he needed to build his elaborate project, Von Schmidt’s fabled dream to build the “Grandest Aqueduct in the World” vanished irretrievably.

San Francisco turned its attention to the Tuolumne River—famously erecting a dam in Yosemite National Park’s Hetch Hetchy Valley—and the rest is history.

The Bureau of Reclamation attempted to appropriate large amounts of Lake Tahoe beginning in 1903, after its engineers realized they needed more water for the Newlands Project designed to irrigate farms in central Nevada near Fallon.

In 1908, the presidential administration of William Howard Taft nearly cinched a contract that would have provided the federal agency carte blanche to drain The Lake for the purpose of feeding water to the Nevada desert and generating electricity for sale. When a forester in the U.S. Department of Agriculture got wind of the project, he mobilized support to wage a prolonged opposition campaign that lasted until 1935. By that time, Lake Tahoe’s perceived role in the public consciousness shifted from an area that was to be exploited for the express benefit of those working in the resource extraction industries to a more contemporary view as a national treasure to be protected and admired.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer and editor.

No Comments